Mosquito - Timothy Winegard's new book a finalist for the Taylor Prize

THE MOSQUITO DETERMINED OUR HISTORY

Review by Herman Silochan - Toronto Caribbean Independent Newspaper

The Mosquito - A Human History of Our Deadliest Predator, by Timothy Winegard

In the past four decades, history has been forced to be dramatically rewritten, over and over, from ancient times to the here and now. The further opening up of archives in the great libraries, monasteries, museums and government records offices of the world is but one avenue for revision. Significantly though, subjecting specimens, species, animal and plant, even relics, to DNA classification and testing has forced re-interpretation on its head. Forensic anthropology and archeology have come into their own.

Those of us who recall our high school history, and later at university, do have a good sense of the sequence of events. But what about the scenes behind the scenes, so to speak?

All of us know that Alexander the Great invaded western India through the Indus Valley, and it was drummed into our heads that his surviving homesick soldiers began to rebel, forcing Alexander to return to Egypt and eventually Macedonia. But is that all? What about extraneous factors, like a toxic climate and exotic diseases?

The great Greek army, probably about 47,000 strong, overpowered foreign adversaries with relative ease, except for one. They couldn’t put down the hordes of mosquitoes in the swamps, lowlands and valleys of the Asian subcontinent. It turns out those little insects were its greatest and most formidable enemy, decimating the numbers, reducing the rest to haggard marching has-been soldiers. They had to turn back.

The local populations seemed to be immune, seasoned as it were to the deadly proboscis puncturing tubes into the skin. An immunity had been built up over centuries. Here, the mosquito was an annoying buzzing ally.

This descriptive analysis it to be repeated over and over. From the great empires, among traders on the Silk Road, colonial conquest, the 19th century degradation of swaths of humanity- called African slavery, its aftermath, civil wars, World War II, right up to right now.

Hannibal was defeated before reaching Rome by mosquitos in the swamps outside the great imperial city. Genghis Khan and his Mongol hordes created a vast land empire for 300 years, but had to demarcate at the gates of Europe: they encountered the mosquito not ever understanding this unseen pestilence. Here the mosquito was an ally of Europe.

Time to ditch the Hollywood versions of real life blockbuster events, and factor in the role of the mosquito to make proper sense of it all.

Time to ditch the Hollywood versions of real life blockbuster events, and factor in the role of the mosquito to make proper sense of it all.

It is true that Union soldiers in the American Civil War prevailed with better equipment and a large economic machine at their backs. However, the paths to battle for all regiments, North and South, was dictated by swamps filled with billions of mosquitos. All commanding officers, generals, down to the lowest private, knew and feared mosquitos; to be bitten invited malaria, typhoid, and ultimately debilitating dysentery.

|

| Timothy Winegard |

You understand African slavery to be more complicated than mere master and unpaid wretched servant, the mosquito created a relationship, that favoured or disfavoured either party.

Building the Panama Canal was one of mankind’s great engineering feat; the main obstacle was not just having to blow up of mountains and dredging lakes, but to withstand the relentless attacks by hordes of mosquitos. The importation of labour to finish this massive project was equally important to replace columns of the dead written in yellow bile and the extensive graves of the first arrivals.

The greatest ally the Americans had in WWII in the Pacific was a breakthrough chemical called DDT, that wiped out mosquitos, but for a brief time only until these insects built new immunities, then re-emerged stronger than ever by the 1960s.

The greatest ally the Americans had in WWII in the Pacific was a breakthrough chemical called DDT, that wiped out mosquitos, but for a brief time only until these insects built new immunities, then re-emerged stronger than ever by the 1960s.

Timothy Winegard is a military historian first and foremost. Having served with the Canadian armed forces, and briefly with the British. That is why this book has a strong sense of the military in almost all chapters. But he is cognizant enough to recognize that standard battlefield, and imperial history, is not only determined by guns and horses, but by mysterious death and pestilence. Lots of it. The mosquito is the main antagonist, and protagonist.

We are introduced to the two main variants of the mosquito, the Ades Aegypti and the Anopheles. The latter pick up parasites from infected people when they bite to obtain blood to nurture their eggs. The former transmits viruses that cause dengue, Zika, chikungunya and yellow fever. We are told from the first chapter, that it is the female mosquito is the enemy, not the male, he just breeds. Within the global mosquito population, there are about 3500 species.

The vectors, or delivery systems varied, but in almost all cases, the swamps and marshes outside towns and cities were recognized as places of infection and watery hell. It was by the18th century that the mosquito was identified as the carrier of death, and by the 19th the fight came from laboratories. A recognition that the cinchona bark from the Americas offered respite lead to massive cultivation in India by 1859. Thus, British army soldiers are having “gin and tonic” as a relaxation drink in their officers’ mess. This life saving fad spread to the grand salons of Europe and the United States.

But immunities are short lived. The fight went on. DDT too had seen its heyday. The long-term effects now haunt us in our agribusiness.

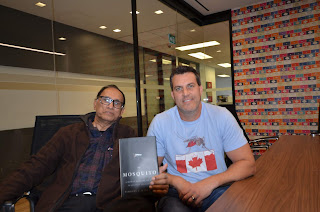

|

| Herman Silochan and Timothy Winegard |

Genetic engineering in our 21st century world has come to the fore. We are fearful of unseen consequences, like recreating the human body with sinister intentions and which are now the stuff of modern TV sci-fi. The real positive side is the elimination of disease. A new attack on the mosquito has begun with promising results.

Enter a program called CRISPR. Basically, it is a technology for editing genomes, altering DNA sequences, and ultimately modifying the gene function. You alter the gene sequence in the mosquito and they won’t reproduce. You create massive swarms of sterile mosquitos, release them into the global insect population, and hopefully you see a reduction in reproduction. Its promising so far. Will mosquitos eventually build an immunity? We don’t know. This resilient creature since time immemorial has survived all sorts eradication measures, it is not to be easily dismissed.

Winegard’s historical account reads like a global whodunnit, enemies one day, friends the next. But you build up insightful knowledge, and you recognize that the story is a never ending one. We await the next chapter.

The Mosquito. A Human History of our Deadliest Predator.

Timothy C.Winegard.

Allen Lane. Penguin Random House.

Comments